We’re just back from an Interrail adventure across Europe. This was a special treat for my 16-year-old to celebrate surviving her GCSEs and for me to relive my youth, albeit with a wheelie suitcase instead of a backpack. It was an incredible time and I could write half a dozen blog posts about it. But most of all I want to tell you about the last day of our holiday, in Munich.

Part of the beauty of our day was that we had no idea what we were doing. Munich was a convenient stopping point on our way home to London from Croatia, where we’d spent five days of shameless beach holidaying. I’d booked two nights in a hotel to give us a full day to explore Munich, and we only did our research at breakfast that morning, while buttering the hotel breakfast bread rolls we were pilfering for our lunch.

Everything is good

This day, like my whole life at the moment, was experienced through the lens of my new and unfolding understanding about God and the nature of the world we live in. I’m on a steep learning curve – every month I seem to come across a book or a podcast or an article which widens and deepens that understanding. Possibly the most significant thing that I’ve radically re-understood of late is that God’s goodness and glory, some would say God’s own self, radiates from every created thing. Not just from things in nature at its most beautiful, but from every atom and electron in the universe.

I’ve now come across this concept in half a dozen different places, but it also came to me independently. I was sitting on my bed one morning to pray, gazing out of the window at the treetops and gardens and birds, and these words seemed to float through the window: Everything is good, because everything comes from God. This phrase came with such a profound sense of peace I felt no need to analyse it there and then; but I find that when I do take it apart, it still rings true.

Munich, cradle of evil

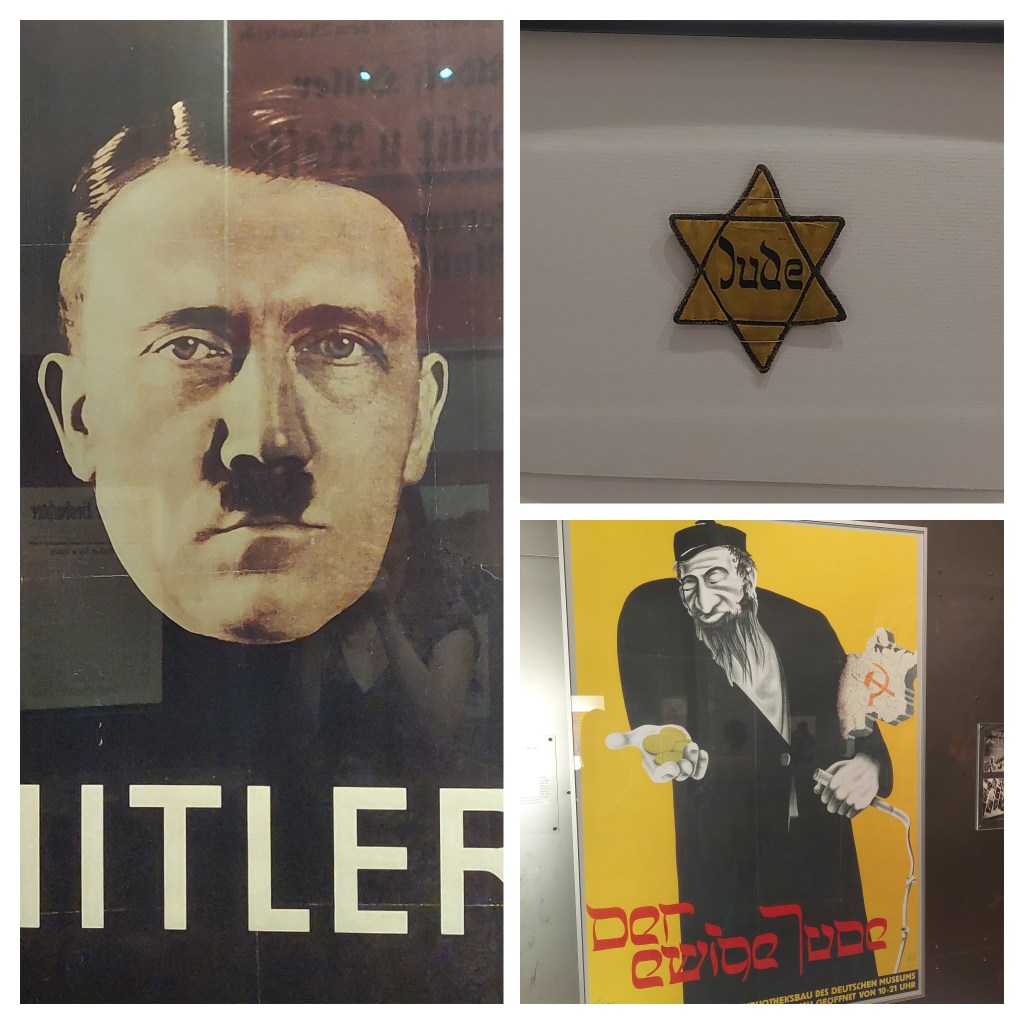

There were three things on our sketchy list that morning and none of them was visiting an exhibition about Hitler’s rise to power in Germany. We just stumbled across the Munich Stadtmuseum while wandering around, and liked the building. It was only 4 euros for both of us to see the two permanent exhibitions, and the staff were very insistent that we should start with the one on National Socialism. So we did. It was sobering and sickening.

Munich is where Hitler built up his National Socialist party from just seven members to millions, and his regime celebrated the city as the birthplace of the Nazi movement. Not many of the labels were in English, but the 16 year old had studied this exact topic as part of her History GCSE, so she was able to explain some of the exhibits – and others needed very little explanation.

There was a machine near the entrance, which I later realised tracks the air temperature and moisture levels in the gallery, but at first I mistook it for an art installation tracking the rise of Nazism in the 1930s, because it ticked away like a time bomb, creating a horrible sense of foreboding.

Exhibits included school children’s exercise books, one displaying a beautifully handwritten poem, ‘To My Führer’; instruments to measure facial features for Aryan characteristics, alongside sample shades of hair; medals for Nazi youth, and for women who had given birth to record numbers of Aryan children; disturbing photos of the nearby Dachau concentration camp; and pictures of the devastation wreaked on Munich during the war, in some cases with weapons that had been manufactured in the city.

What moved me most about the whole exhibition was that it exists at all. Here is a city and nation saying openly, “Look what we’ve done. Look what we gave birth to. This terrible thing started right here. Come and see.” No hiding, no cover up, just the honest, god-awful truth – and they want it to be known. I have boundless admiration and respect for that honesty. I know people whose lives and relationships have been wrecked, not so much by the mistakes they made, but by refusing to admit to those mistakes. Surely nations are the same, and surely this honesty about the past is needed in 2020s Europe more than ever?1

The river

From there we meandered along to the Englisher Garten, which was on our list, billed as being larger than Hyde Park. It also boasted a river. We’re keen on swimming in rivers, the 16 year old and I, and the absolute highlight of our time in Vienna the week before was a blissful dip in the Danube. But the one article we read on things to do in Munich warned us off swimming in this river. The current is too strong, too dangerous, it said. So we felt slightly ripped off when we arrived, sans swimsuits, to see the river full of Germans not so much swimming as being swept along by said current, laughing their heads off.

Still, it was fun to watch, especially as we had ice cream (and especially as that ice cream was sold from a machine that had been pedalled to the park, rather than a stinky diesel van).

Beer hall: temple to joy

Next on the list was the Hofbrauhuas, Munich’s famous beer hall. With its vaulted ceilings and stained glass windows it felt like a church – a really fun church with a jolly oompah band (note the lederhosen), waitresses in traditional dress offering baskets of jumbo pretzels, and beer glasses bigger than your head. I had the ‘half’ size (yes, the 16 year old has my drink in the photo. She tried it and didn’t like it) and it must have contained at least a pint.

Even before I drank the very nice ‘dark beer’ with our meal, I began to feel slightly intoxicated. Why? Because this place felt like a temple to joy. It was a celebration of food, drink, music, friendship. I was with one of my favourite people in the whole world. People were eating, drinking, laughing, taking group selfies – humans at their happiest and best. I see all this as a gift from God. He gives us the capacity for enjoyment and then, far more often than we acknowledge or are grateful for, he fulfils it. When the band was in full swing, it felt as though everyone should be up and dancing, or at least swaying in time in their seats. But that urge was satisified later, as you’ll see.

Dancing in a palace garden

Budget exhausted by the beer hall, we headed off into the evening sunshine to see what fun was left to be had. We found ourselves near Das Residenz, a palace we had seen advertised as a tourist attraction and dismissed because of the entry fees. But as we rounded a corner we realised that the gardens are open to the public for free. We followed others through an archway and the beautiful formal palace gardens opened up around us. This was a lovely discovery in itself, but then we came across this…

It was a pergola, if that’s the right term, full of people dancing. Music was coming from somewhere and couples were salsa dancing with various degrees of competence. (Out of shot, a young woman is dancing with a man who was at least 70.) It looked wonderful. The 16 year old and I stood and stared for a while, then looked at each other, dumped our bags and joined in. We danced together, copying the other couples’ footwork as best we could. Then we spotted a woman on her own in a yellow dress who looked like she knew what she was doing. We approached her and yes, she did speak English, and yes she could show us how to dance. She danced with my daughter, and a friend of hers took pity on me and offered to be my partner. After a few minutes we swapped over. Together we learnt the very basic steps and it all kind of worked.

One moment is crystallised in my mind. I am holding onto my partner, probably gripping his shoulder a bit too hard with the effort of concentrating on my feet, and I look across at the 16 year old. She is dancing with the woman in the yellow dress, smiling. It’s July. The evening light is streaming into the beautiful pergola and lighting up dancers and shining on the tiled floor. We have music. We have bodies and we are moving them in time, more or less. We are holding onto each other, recognising each other’s strength and beauty, enjoying being alive together. It fills up my heart again now to think of that moment – relishing a gift that we had stumbled across, unplanned, free. It was pure joy.

And again: everything is good

Until fairly recently, I think my evangelical Christian worldview led me to see – at a fairly unconscious level – the world and human society as fundamentally wrong. And yes, I would still say there is a profound lostness and brokenness, sometimes even evil. The horrors of Nazism and World War II don’t leave much room for doubt about that. But what I see now is that fundamentally, at the core of every thing and every human being, is a deeper goodness: the glory of God. That has not and cannot change. The lostness, the evil, the depravity, is something which has crept over us like a disease or an occupying army – it isn’t who we are and doesn’t change the nature and value at our core. 2

Now, increasingly, it’s the glory at the heart of all things and all people that strikes me. My awareness of it is growing and outshining the rest. Desmond Tutu said “We are made for goodness. We are fundamentally good. …that’s who we are at our core. Why else do we get so outraged by wrong? …Evil and wrong are aberrations… The norm is goodness.”3 Nazism was a devastating force for evil that reigned for a while, but in time it was overcome, and now it lies exposed by the more powerful forces of peace and justice. Other evils like it come and go and wreak their havoc, but they cannot outlive the good. I keep coming back to that idea from Martin Luther King Jr: the arc of the universe is long, but it bends towards justice.

How can I respond to glimpsing this deep, profound goodness, and the almost uncontainable joy it brings? I knew what to do as soon as I got back to London. My life is made up of too many things that need to be done, either out of duty, or because I want to change the world. There aren’t many things I do regularly that will achieve absolutely nothing except a good time. So I’ve put that right – I’ve scheduled in some joy. This Friday I’m going to my first salsa class 🙂

- My mother told me recently that she hitchhiked around Europe with three friends as a youngster in the early 60s. They went to Munich and made friends with a German girl, whose parents took them all in for a few nights. This girl later came to stay with my mother’s family in Dublin. One evening they took her to ‘the pictures’ without checking first what film was showing. It was a war film. You can imagine how the Germans might have been portrayed. She sat there and sobbed throughout. ↩︎

- I’ve read that these are the illustrations used by Pelagius, who taught in the 4th century that nature and humanity are fundamentally good, not fundamentally depraved – though still very much in need of grace. This rejection of ‘original sin’ has always been accepted by the church in the East, but the church based in Rome excommunicated him for this teaching and smeared him as a heretic. (I think there was a bit of racial prejudice going on because as a Welshman living in Rome his haircut and eating habits were offensive to the Roman Christians.) See the brilliant book Sacred Earth, Sacred Soul by John Philip Newell for more. ↩︎

- Made for Goodness, Chapter 1 ↩︎